Stained Glass

When St Michael’s was consecrated in 1876, it had no stained glass, and as late as the previous year there had been a strong suggestion that the new church should be dedicated to St Mary the Virgin. It is to the final decision in favour of St Michael and All Angels – backed by the generous benefactor Frederick Scudamore of the Manor House on the opposite side of Tonbridge Road – that we owe our programme of angel windows in the north and south aisles, which is unusual both in its overall conception and in many of its details.

The first windows you see on entering the church are, however, those of the baptistery – the first ones to be installed (1880), paid for by the collections at children’s services. The subjects (Noah’s ark, the Israelites crossing the Red Sea, the Baptism of Christ and His ministry to children) are all, for Christians, linked to the sacrament of baptism, by which those in search of salvation “enter the Church” in its fullest sense.

On coming into the body of the church, the eye is caught (particularly in the morning) by the east window, presented by Scudamore and installed in 1880. This and the two angel windows in the chancel are by the eminent Victorian firm of Heaton, Butler and Bayne, who often worked in association with Arthur Blomfield, the architect who designed St Michael’s. This window was inspired by Matthew 25, 31: “When the Son of Man shall come in his glory and all the holy angels with him, then shall he sit upon the throne of his glory…” The next few verses warn of the last judgement, and this window, besides the vision of Christ enthroned and the multitude of angels surrounding Him, includes motifs indicating that the judgement is just about to begin: two angels are sounding trumpets, while in the foreground the Archangel Michael holds the scales in which he was traditionally imagined weighing souls on judgement day. Above is an Agnus Dei, symbol of the risen Christ, sacrificed and triumphant.

The angel windows of the two side aisles were planned on the basis that the north side, with its more subdued light, should be devoted to Old Testament angels, and the south side, which receives the full blaze of the sun, to New Testament ones – just as, in Christian thought, the light given by God to the Jewish people in Old Testament times pointed forward to the appearance of Christ as the Sun of Righteousness. In the Old Testament we often meet the expression “the Angel of the Lord”, the idea being that the angel figure is frequently a manifestation of the immediate presence of God – hence those who encounter him are surprised to find themselves still alive. In the New Testament the emphasis is generally more on the idea of an angel as a messenger (which is what the Greek word angelos means) bringing good news, or comfort, from God to human beings.

Like those of the baptistery, this group of windows, – installed between 1882 and 1890, the Old Testament ones preceding the New – were commissioned from Hardman & Co. of Birmingham, and were probably designed by, or under, John Hardman Powell, son-in-law of Augustus Pugin. In places where we might expect more movement, they sometimes seem rather static, but they are remarkable (with occasional exceptions) for their faithfulness to the text of the Bible.

Both series are, in narrative terms, in chronological order going from west to east (towards the rising sun, the altar and the last judgement).

Starting at the west end of the south aisle to begin the sequence of New Testament angels. In fact these were executed and installed in the reverse of the narrative order – again an indication that the sequence was planned in advance in its totality. These too are all by Hardman & Co. You will first notice the west window of the aisle, presented in memory of the first vicar of St Michael’s, showing the war in heaven (Revelation 12) in which Michael and his angels cast out the devil and his angels. The portrayal has its limitations, but the effect of the colour when the afternoon sun catches it can be spectacular.

South Aisle

|

“Fear not, Zacharias, for thy prayer is heard.” The angel Gabriel stands “on the right side of the altar of incense” (our left as we look at the window) as the elderly priest Zachariah, holding a thurible, makes the appointed offering of incense in the temple. Note the six-winged seraph pictured on the hanging behind the altar. Gabriel brings from God the message that Zachariah and his wife Elizabeth, hitherto childless, will have a son – John the Baptist (Luke 1). |

|

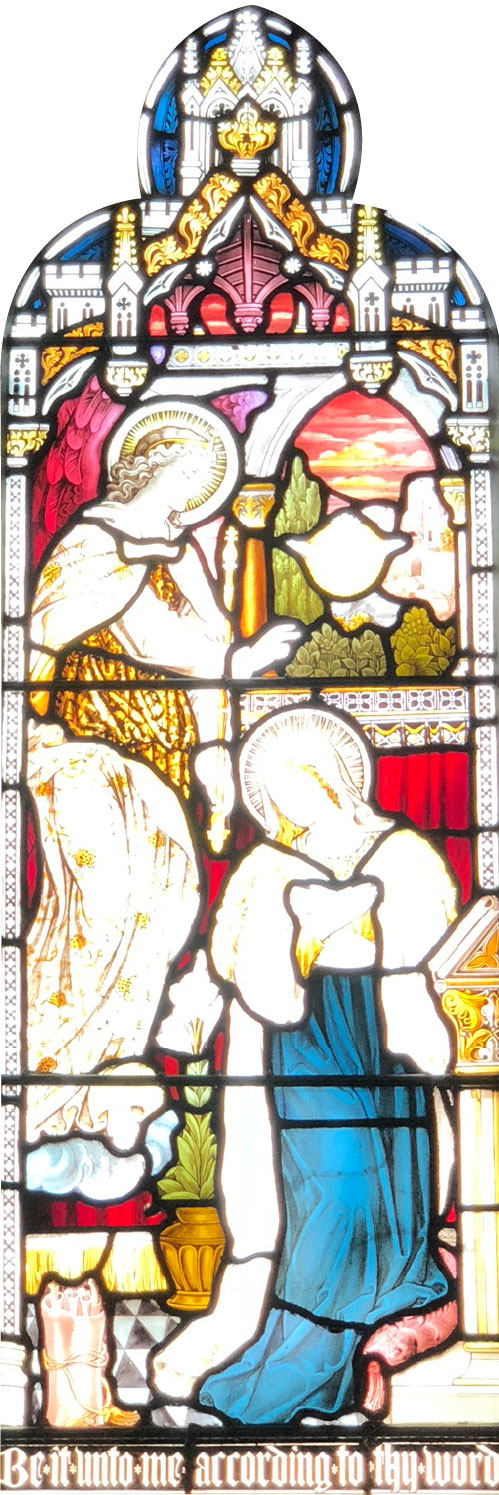

“Be it unto me according to thy word.” Mary has been praying or meditating on the Scriptures which contain the promises of God – note the open scroll on her prayer-desk and the rolled-up scroll in the left foreground. A potted lily, symbolising her purity, stands beside her. Gabriel, bearing a herald’s wand, brings the message that through the Holy Spirit (seen entering through the window in the form of a dove), Mary is to be the mother of the Saviour. Mary responds in loving obedience as, outside the window, the sun rises over Nazareth (Luke 1). |

|

“The angel appeared to him in a dream.” The troubled Joseph, sitting at night in his carpenter’s shop, has dozed off with a rolled scroll on his bench – perhaps the prophecy of Isaiah, which Matthew quotes immediately after this episode. Note the details of the workshop – down to the wood shavings on the floor. The angel, again bearing a herald’s wand, brings a message of reassurance: Joseph should bring Mary home as his wife, because her pregnancy has come about through the Holy Spirit (Matthew 1). |

|

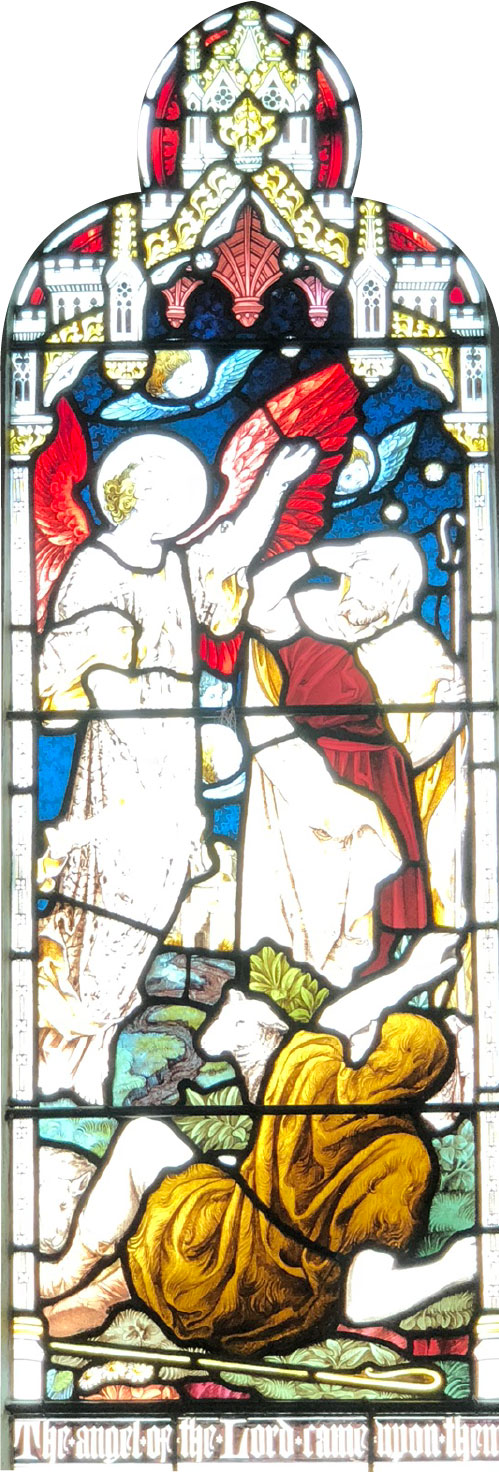

“The Angel of the Lord came upon them.” Two shepherds, dazzled and frightened, receive the angel’s message about the birth of the Saviour in Bethlehem. Four winged heads in the sky represent – in a rather limited way – the multitude of the heavenly host singing “Glory to God in the highest” (Luke 2). |

|

“Angels came and ministered unto him.” At the beginning of His ministry, Jesus has spent forty days fasting in the wilderness and confronting a series of temptations. This window emphasises that, though victorious, He is exhausted; one angel is supporting him and another arrives with a platter of fruit. Although the detail of the wild beasts (here a lion and a bear) is taken from Mark, the text chosen is from Matthew 4. |

|

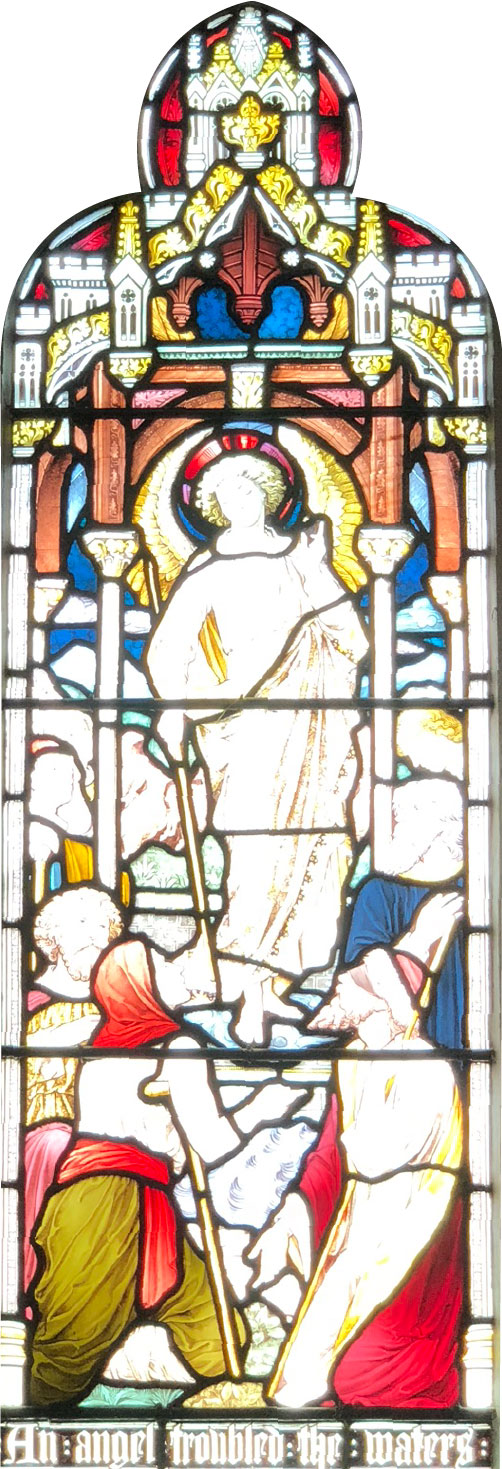

“An angel troubled the waters.” An unusual subject: this is the pool of Bethesda at Jerusalem. Occasional periods of turbulence in the pool were attributed to the activity of an angel, and when these occurred, the pool had healing properties for a sick person who could get into it immediately. According to John’s Gospel, this was the setting of a miracle performed by Christ – independently of the angel or the pool – to heal a disabled man who had no one to help him into the water. In this window, the pool is being disturbed (note the waves), but Christ is yet to arrive and the disabled man must be among the waiting figures in the foreground. Sheep are visible in the background; the evangelist says that the pool is “by the sheep market” (John 5). |

|

“There appeared an angel strengthening him.” Knowing that He is soon to be put to death, Christ, accompanied by his disciples Peter, James and John, has gone to the Garden of Gethsemane to pray on the night of His betrayal and arrest. The disciples are unable to stay awake, and the kneeling Christ is supported by an angel as He prays in agony that if possible the cup may pass away – but that God’s will may be done (Luke 22). |

|

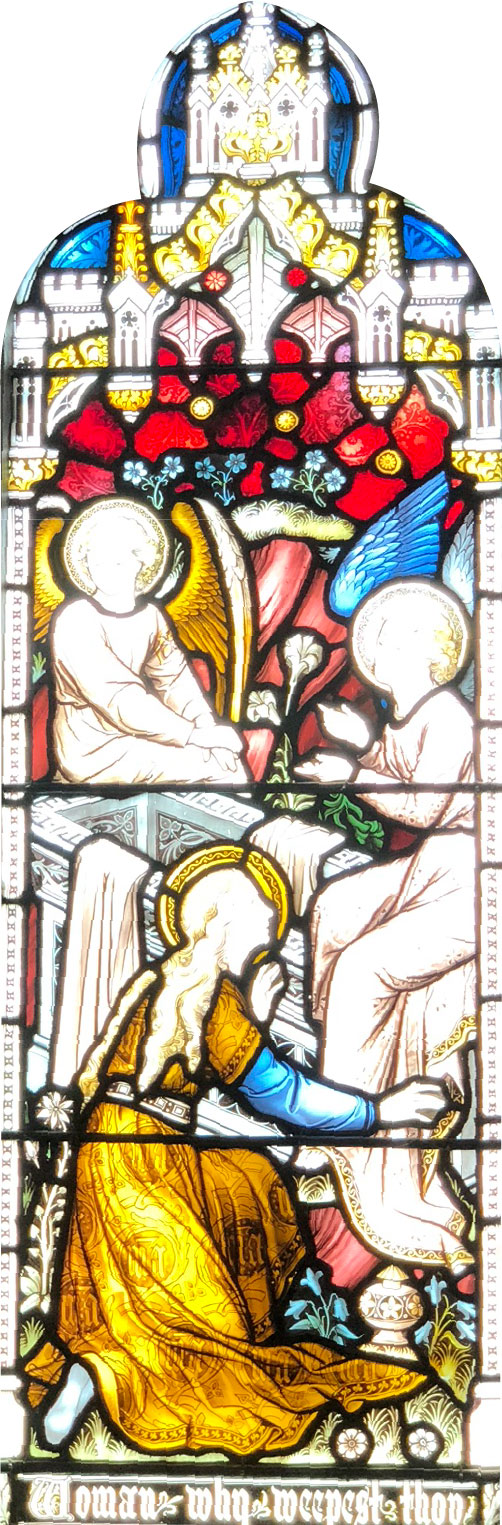

“Woman, why weepest thou?” On the first Easter morning, St Mary Magdalene (often pictured, as in this window, with her hair loose and with a pot of ointment) is standing at the empty tomb weeping, because she believes that the body of Jesus has been taken away. Looking into the tomb, she sees two angels sitting at the head and foot of the place where the body had been. In John’s account of the Resurrection, the angels do not deliver a message; Mary turns away and is at once confronted with the risen Christ Himself (John 20). |

|

“Two men stood by them in white apparel.” The apostles, shown on their knees looking upward, have just seen the victorious Christ ascend into heaven. Some portrayals of the Ascension show a last glimpse of Christ’s feet disappearing into the clouds, but here the focus is on the message of the angels: they promise that just as Christ has ascended, so He will come again (Acts 1). |

North Aisle

|

“He drove them out”. The disobedient Adam and Eve are expelled from Paradise by an angel whose robe, curiously, seems to be inscribed “Alleluia” (Praise the Lord)! In most illustrations of this story the angel is shown in the garden gateway with the flaming sword mentioned in Genesis 3, 24, but here he has no sword. Perhaps the “Alleluia” is meant to remind the viewer that only through the fall of the human race could its redemption by Christ have taken place. Notice how Adam and Eve (dressed in animal skins) are stepping, barefoot, from a place of grass and flowers into a place of thorns. Unusually and poignantly, the artist shows the serpent travelling, now “on his belly”, out into the world alongside them (Genesis 3). |

|

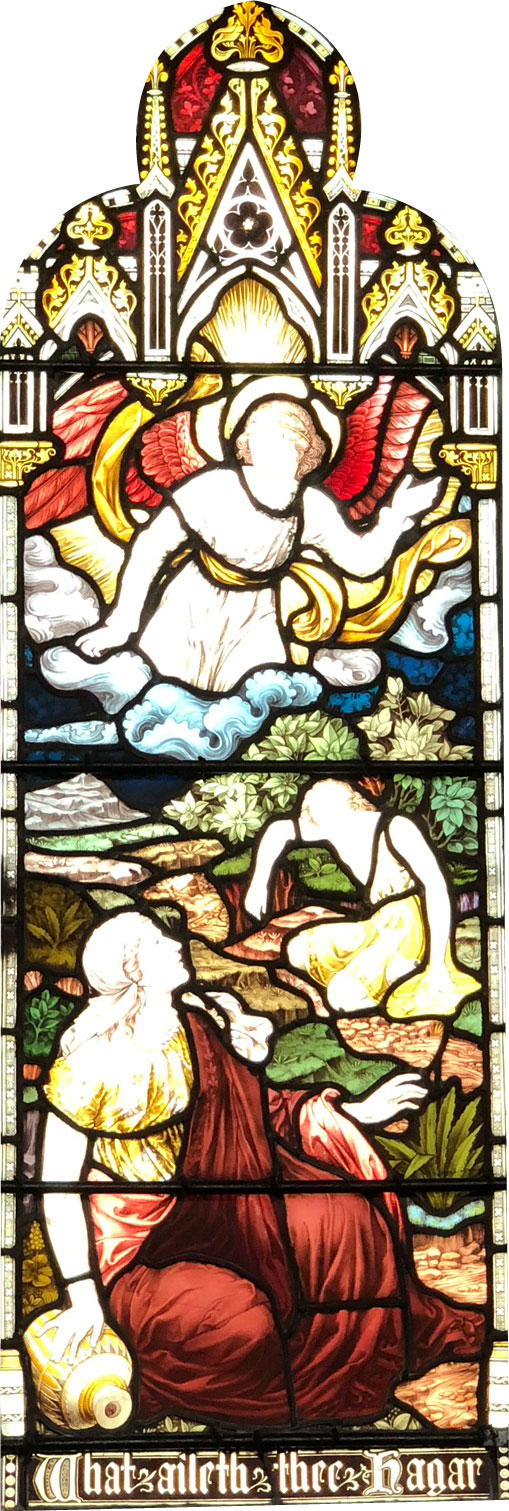

“What aileth thee, Hagar?” Abraham has become the father of a son, Isaac, by his wife Sarah. His Egyptian slave-woman, Hagar, had previously borne him a son, Ishmael. A family disagreement has led Abraham to turn out Hagar, with Ishmael, into the wilderness, where Hagar leaves her child under a bush and moves away to avoid seeing him die of thirst (note the empty water-bottle). An angel calls to her “out of heaven”, telling her that God has heard the child’s cries and that Ishmael will be the ancestor of a great nation (traditionally the Arabs). She then sees “a well of water” (note the glimpse of blue water to the right of Hagar), and the wanderers drink and survive. Ishmael is shown here almost as an adolescent (a previous passage puts his age at 13), whereas the actual text of this episode suggests that he was a child in arms (Genesis 21). |

|

“’Abraham!’ and he said, ‘Here am I.’” A few years afterwards, Abraham is tested when God commands him to sacrifice Isaac as a burnt offering, despite having earlier told him that He had a particular promise and plan for Isaac’s descendants. At the moment when Abraham has drawn the knife to slay his son, the angel calls to him and tells him not to touch Isaac – here the artist shows the angel actually grabbing Abraham’s arm to stop him. Abraham then sees a ram entangled in a thicket, and sacrifices the ram instead. Note the portable fire-pot on the right. Abraham here is surrounded by stars – probably a reminder that later in the same chapter, God promises to Abraham descendants as numerous “as the stars of heaven” (Genesis 22). |

|

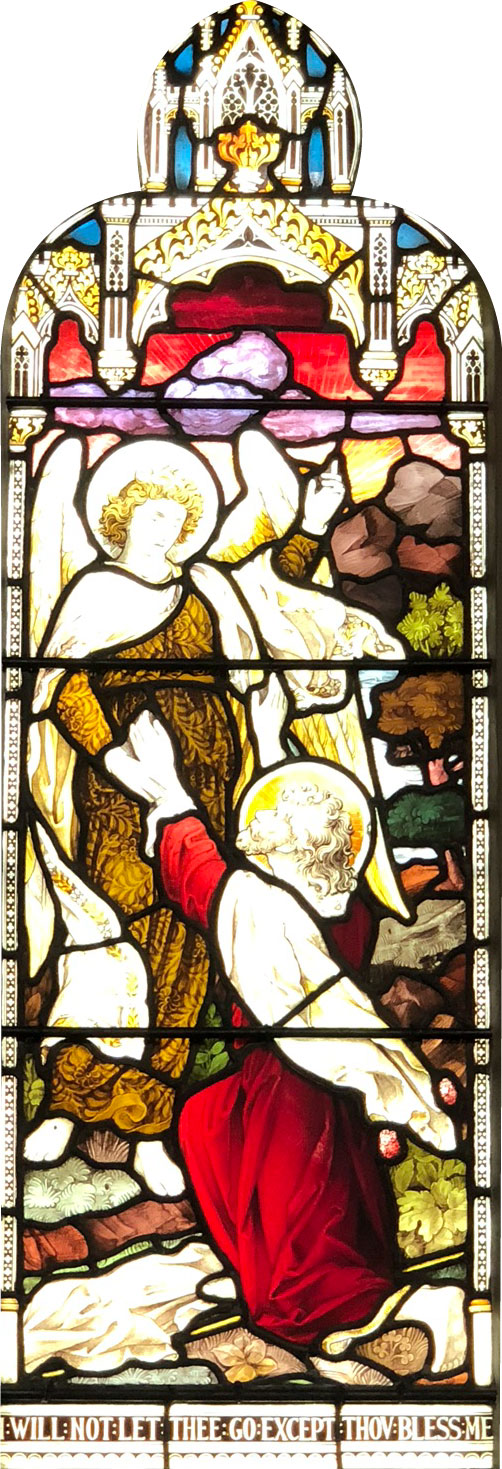

“I will not let thee go except thou bless me.” Neither figure here is dressed for wrestling – Victorian sensibilities at work perhaps – but in the story illustrated in this window, Isaac’s son Jacob wrestles during the night with a mysterious stranger, who tries to disengage from the struggle as “the day breaketh” (notice the dawn sky in the background). Jacob hangs on, demanding a blessing, and the stranger, evidently the angel of the Lord, gives him the new name of Israel (one who strives with God and prevails) and blesses him. Jacob recognises that he has seen God and nonetheless survived (Genesis 32). |

|

“The Lord is with thee, thou mighty man of valour.” The divine plan unfolds and Israel’s descendants have become a nation. They have turned their backs on God and now, oppressed and pillaged by the Midianites, are pleading for God to rescue them. Gideon, threshing his corn “by the winepress” (notice the grapes growing around the building) to conceal it from the raiders, sees an angel of the Lord “sitting under an oak”. The angel tells the reluctant Gideon that God has chosen him to save his people (Judges 6). |

|

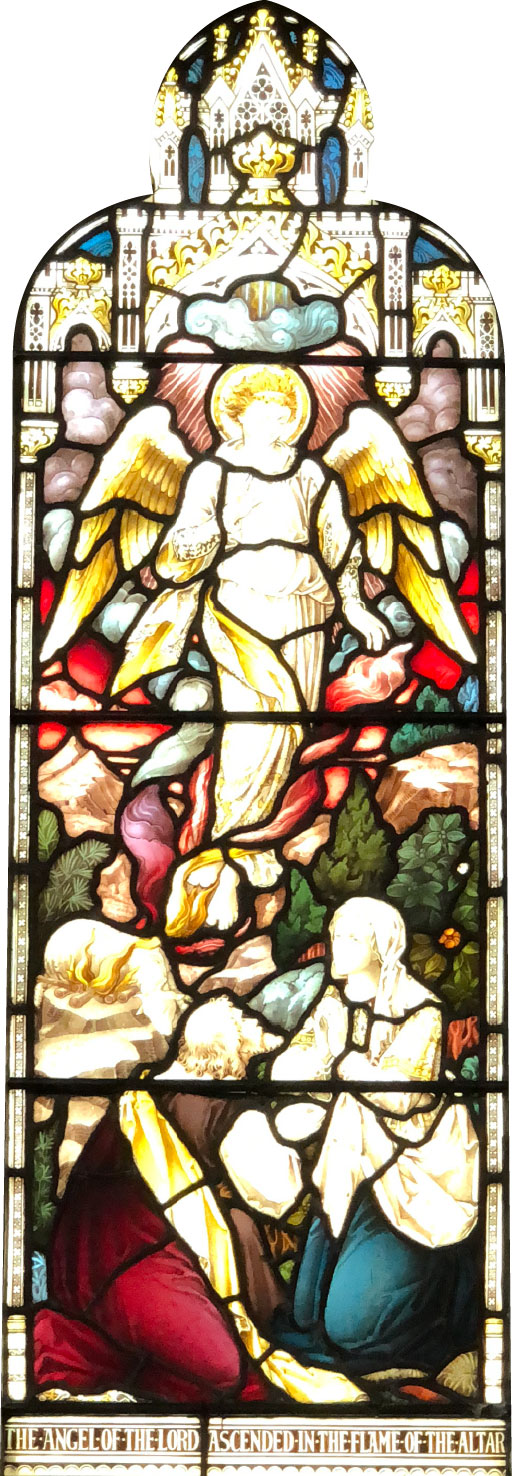

“The angel of the Lord ascended in the flame of the altar.” A stranger has promised Manoah and his childless wife a son, and gives them strict instructions about his upbringing. Manoah sacrifices a kid “upon a rock” and the stranger reveals himself as an angel by mounting heavenward in the flame, as Manoah and his wife kneel in prayer. The promised child will be the hero Samson. (Judges 13). |

|

“The angel of the Lord stood by the threshing floor of Ornan.” Because King David (crowned, on the left) has displeased God, a destroying angel is smiting the land with sickness, which is now threatening Jerusalem (visible in the distance). David sees the angel with a drawn sword, standing near Ornan’s threshing floor, and there the repentant king offers sacrifice and the angel sheaths his sword. The other characters here are Ornan (on the right) and a shadowy figure behind David – presumably Gad, David’s seer (1 Chronicles 21). |

|

“An angel touched him and said, ‘Arise and eat.’” The prophet Elijah, fleeing for his life into the wilderness from the hostile King Ahab and his sinister queen Jezebel, is sustained by an angel when he has fallen asleep under a juniper tree, ready to give up. When the angel wakes him, he finds a vessel of water “at his head” and “a cake baken on the coals” (on the right). This food gives him strength to travel on for forty days and forty nights (1Kings 19). |

|

“The angel went out and smote the camp of the Assyrians.” The Assyrian king Sennacherib has come with his army to attack Jerusalem (on the left), but the angel of the Lord strikes the attackers with pestilence, they perish in their thousands overnight, and Sennacherib departs (2Kings 19). This story is the basis of a famous poem by Byron. In windows 7 and 9 the drawn sword indicates the destroying angel. Presumably the Old Testament sequence was planned as a whole, though executed over 4 years, and the absence of the flaming sword in window 1 might also indicate a distinction the artist wanted to make: the angelic guard of Genesis 3 is not a destroyer. |

Make your way into the chancel and you will see two other angel windows not easily visible from the nave. Installed in 1881, they show the archangels Michael (on the south side), and Gabriel and Raphael (on the north). The latter two-light window was given in memory of the wholesale grocer Charles Arkcoll,; St Michael was paid for by the church’s Stained Glass Window Association, which also financed the Adam and Eve window in the north aisle.

The windows in the small Ascension Chapel on the north side of the church are a less coherent group. The one on the north side of the altar is said to represent the healing of the woman with the issue of blood (Mark 5), but if so, it seems, judging from its garden setting, to have been adapted with minimal alteration from a design for the much more usual subject of the meeting of Mary Magdalene with the risen Christ – “Touch me not, for I am not yet ascended”. The corresponding window on the south side shows a child presenting a bunch of flowers to Christ and recalls His words “Of such is the Kingdom of God.” In the trefoil at the top of this window we see “a pelican in her piety” – a symbol of Christ commonly used in medieval art because it was once believed that the mother pelican gave life to her brood by wounding her breast and feeding them with her own blood, just as Christ poured out His blood to give life to the world.

The large window on the north side of the chapel, showing the ascended Christ as priest and king, was unveiled in 1921. The figure of Christ is flanked by those of St George, patron saint of England, and St Alban, honoured as the first British martyr, each bearing his own banner. The wading birds in the bottom right-hand corner of the St Alban light may refer to the legend that a river parted its waters for St Alban on his way to execution. After the end of World War I, there was much discussion about whether a war memorial should be placed in the grounds of St Michael’s, but the final decision was to install this window in memory of the fallen from this parish. A plate at the entrance to the chapel bears their names.

As you go back down the church, enjoy the lofty twin west windows, designed by Heaton, Butler & Bayne and presented in 1898 by the widow of Lewis Davis Wigan of Oakwood House. They depict four miracle stories related in the gospels: the stilling of the storm and the marriage at Cana (Mark 4, John 2) on the north, and blind Bartimaeus and the man with the palsy (Mark 10, Matthew 9) on the south.